Sandro was interviewed in the November issue of the Italian discography magazine Falstaff.

What follows is an English translation of the interview.

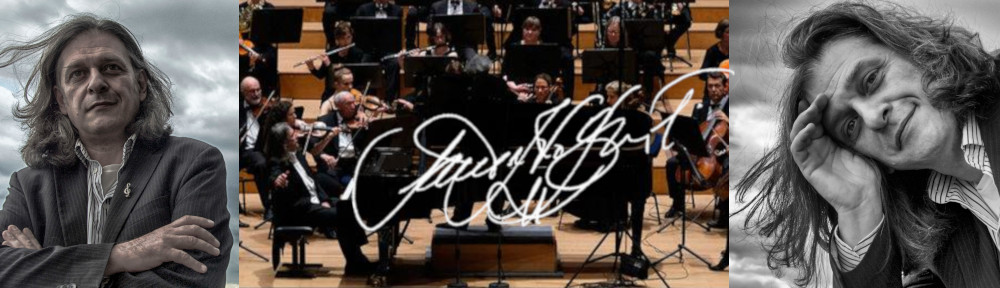

As a true Tuscan, Sandro Ivo Bartoli is an excellent raconteur, extroverted and secure without appearing arrogant nor superior. A mirror of these trademarks is apparent in his recordings, true interpretative tours de force realized with passion and presence. More known abroad than in Italy (a classic…) and coming from a twenty years spell in Great Britain, Sandro Ivo Bartoli was a pupil of the great Shura Cherkassky; he has played all over the world and is recognised as the leading interpreter of early twentieth century Italian music. His last CDs, for Brilliant Classics, are devoted to Busoni (the monumental Fantasia contrappuntistica and the Seven Elegies, plus the Liszt Transcriptions) and Respighi (the splendid Toccata for piano and orchestra, here recorded for the first time together with the Concerto in modo misolidio).

THE ENGLISH PIANIST

by Ennio Speranza

Falstaff: Your musical training, and your life, has been divided between Italy and England. How did it happen that you moved from the Florence Conservatoire to the Royal Academy of Music?

Sandro Ivo Bartoli: Very often the circumstances that dictate our future are fortuitous. In Vecchiano, the little village near Pisa where I was born, I met a friend who had emigrated to England in the Sixties. He offered me a lift to London in his sports car (it was a Mercedes Pagoda) which I accepted happily. Once in London, I went to practice at the Yamaha Piano Studios, just around the corner from Oxford Circus. There, I met an agent who offered me several concerts that same summer. Then, a Russian teacher persuaded me to take the entrance examination at the Academy. What should have been a trip of a couple of weeks turned in a three months stay. In December of that year I won a place at the Academy. I came back to Italy just to get my diploma, then packed my bags…

Falstaff: How did your collaboration with Shura Cherkassky began?

Bartoli: At the Yamaha Studios there was a man who seemed like a character of Kundera. His name was Jiri Koneckny, he was a competent pianist with a notable musical culture, and could speak fluently every European language. I used to spend many hours with him, listening to historic recordings. On Sunday, October 13th 1991, he called me around 10 in the morning: «You must come immediately to the Festival Hall: Cherkassky is playing». I didn’t even know who Cherkassky was, and my attempts at dodging the concert due to tiredness proved futile. At 3.30 I sat in the choir of the Festival Hall. Cherkassky entered and began playing the Bach-Busoni Chaconne. It was a revelation, one of those moments that change a life. Within the sixth bar I was in tears: truly a piano could sound like that? I had read in a magazine that Cherkassky lived at the White House Hotel, a stone throw away from my accommodation in Albany Street. I mustered some courage and wrote to him a sincere letter. Three months later, my phone rang: it was him. We became friends on the spot, and for the next four years we met regularly. For months and months on end he refused to hear me play. He said that I was too instinctive, and that he could teach me nothing. Then, one day, he proclaimed that he would give me a lesson. I played the Chaconne, and the lesson went on for six hours. From that point on, there were no more ‘lessons’, but rather a sharing of his piano. He would practice for an hour, then I would practice for an hour and so on. Sometimes, he would come up with pearls of wisdom. «Technique is like money – he once told me – you must have it, but more importantly you must know how to spend it». I learned more from those afternoons than from my entire schooling.

Falstaff: The range of compositions that you perform, albeit large, denotes a preference or a special predilection for the Italian repertoire of the early twentieth century. What attracts you more of this repertoire?

Bartoli: The fresh inventiveness! In Italy, we were coming from two hundred years of operatic ‘dictatorship’, and we lacked a proper symphonic tradition. We owe the renaissance of Italian instrumental music to such maestros as Respighi, Malipiero, Casella and others. The beautiful thing was that, because these composers were not burdened by the weight of a romantic tradition, they were able to express their ideas in a fantastic, free way, without having to pay respect to the past. In the best cases, the results were miraculous: I think of the last two concertos of Respighi, to A Notte Alta of Casella, of the concertos of Malipiero, but also of Pizzetti’s Canti della stagione alta.

Falstaff: The music of Respighi, Casella, Busoni, Malipiero, Pizzetti, needs a revival or in many cases we could speak of ‘discovery’, seeing how much it has been neglected in the past?

Bartoli: Nowadays there are very few people indeed who know the work and aesthetic of these maestros. However, believe me, their output is valid and convincing. Above all, this music offers expressive possibilities of the first order. A few years ago the great Aldo Ciccolini initiated a polemical debate in the Italian specialized press, accusing it of sectarianism against the Generation of the Eighties. I tried to contribute with my thoughts, but you know… I was a young pianist building a career, and my opinion didn’t interest anyone. Today I notice a renewed interest in this repertoire, which gives me a great satisfaction.

Falstaff: I have the impression that in England and in the English speaking world there is more attention towards thee Italian composers. Is it true?

Bartoli: Inevitably! In Italy we live in this disconcerting cultural bubble. Our audiences are not used to reason with critical spirit anymore, and at music does not have a clear cut place in our social culture. It is a great shame. You must realise that almost always, when I play in Italy, my audience keeps telling me that I should play a more ‘tuneful’ repertoire. I have had more understanding and appreciation in Germany, in France, and even in the USA than in here! In any case, it is enough to have a look at my discography: I recorded Malipiero and Casella for the ASV label, the Malipiero Concertos for CPO, the concertos of Respighi and solo works by Busoni for Brilliant Classics. All foreign labels…

Falstaff: What is the most difficult piece, both amotionally and technically, that you have tackled? I suspect it to be the Fantasia contrappuntistica of Busoni, but I’d like you to tell me something about it.

Bartoli: The Fantasia contrappuntistica is like the leaning tower of Pisa: everybody knows it, but it is a little bit too far off the beaten track for the casual tourist who prefers going to Rome, Florence, or Venice, just as we pianists tend to prefer investing the enormous interpretative effort that the Fantasia requires on works which have a greater impact on our audiences. Technically, the Fantasia presents the full gamut of fiendishly complex writing that a virtuoso such as Busoni could conjure up. The greatest difficulty, for me at least, can be found in the hidden meaning of this visionary music, in the blend of esoteric sonorities that Busoni drapes around the original idea of Bach. The Fantasia is a voyage that is always different. You could interpret it ascetically, romantically, even with a certain detached objectivity: and it always works! I have a particular attraction for complex music and the interpretative difficulties that they present. Among these, the Fantasia contrappuntistica sits atop the highest pinnacle without a doubt.

Falstaff: Can you tell us about your relationship with the author Antonio Tabucchi, with whom you have collaborated? How did it start?

Bartoli: Antonio Tabucchi was also born in Vecchiano, and I was a school friend of his famous photographer son Michele. Years ago, after a concert, Antonio asked me to accompany him to Paris, at the Centre Georges Pompidou, to play Italian music in conjunction to a lecture he was giving. I offered Casella and Malipiero, which were received with much acclaim. Later, I took care of the musical aspect of a beautiful project: Antonio’s theatrical adaptation of Fernando Pessoa’s ‘Book of Disquiet’ at the Avignon Festival. It was an extraordinary experience.

Falstaff: In one of your most recent records we find the Concerto in modo misolidio and the Toccata of Respighi, a piece of which you gave the first modern performance in 1993. What is so special about this last work and how do you rate it among Respighi’s production?

Bartoli: The Toccata is a composition to which I am very close: with it I gave both my BBC debut and my American debut, and over the years I have had the opportunity to revisit this music several times. The Toccata is a masterpiece, a piano concerto in all but the title. It is the last work that Respighi wrote for piano and orchestra, and probably his best in the medium. Two slow movements, solemn in their contrapunctal structure and archaic in their melodic spirit, lead to the impetuous final allegro vivo which closes the work. It is immediate music, expertly written, and full of that Italian lyricism that Respighi impersonated so vividly. To play it is very fun, but I wonder how many kids from the Italian conservatoires know it…

Falstaff: If you had to choose the best piano composition from the Italian repertoire of the early twentieth century, which would you select? And why?

Bartoli: With the exception of the Fantasia contrappuntistica, which cannot be said to be ‘italian’ music if not for the Passport of its composer, the choice is quite difficult. I can think of three things. For the virtuoso pianist, seeking a showpiece, Casella’s Toccata Op.6 would be the right choice. Brilliant figurations, à la Scarlatti, and adventurous harmonies make it an exciting piece and very idiomatic. Malipiero’s La Notte dei Morti is a tragic poem, its vivid colours filtered through a black screen. It is a sonorous marvel, and very representative of its author’s aesthetics. Pizzetti’s Sonata 1942, on the other hand, is perhaps the most noble expression of poetic lyricism that was made possible by the lack of a romantic tradition, as I was saying before.

Falstaff: You are also a passionate researcher. Are there Italian composers who are not known or seldom performed that would deserve a discographic project?

Bartoli: There are for sure! I am convinced that our libraries house scores of masterpieces from the past that should be revived. There is no need to go back in time so much: it is enough to stop at the Twentieth Century. I can think of a name, that of Vittorio Rieti. He was an agile composer, who developed a neoclassical idiom that was at once fascinating and refined. He emigrated to the United states and died there in 1994, at the age of 97. And today he is pretty much forgotten.

Falstaff: The last and inevitable question: future projects…

Bartoli: Before the end of the year I would like to make a start on the first volume of Tchajkovskij’s complete piano works, which I will recored for Brilliant Classics and that I’d like to record in the Teatro dei Differenti in Barga. Since I came back to Italy, I became passionate about our historic opera houses, which are a unique architectural heritage that we do not exploit enough. Whenever I can, I try to bring back great music to these wonderful temples of the arts. Recently, together with a group of friends and colleagues, I founded the Accademia de’Concerti, a music society that promotes excellence in classical music using to the full the resources that the historic opera houses can offer in terms of acoustics and logistics. I will devote the summer to the Accademia, then I will resume my travelling: in the autumn I will play Rachmaninov’s Second Concerto with the State Orchetra of Saxony under my friend Michele Carully, then, among other things, I will play Liszt’s Malédiction concerto in Bad Elster on a piano that used to belong to Josef Hoffmann. Next year there will be more news, especially in the record market, but these I will tell you on another occasion….